HFSP Long-Term Fellowships are awarded to postdocs with a Ph.D. in Biology who want to embark on a novel and frontier project in the life sciences. Together with the HFSP Cross-Disciplinary Fellowships, they foster the next generation of life science research, last for three years, and on average provide $200,000 USD in total. Fellows work in a host laboratory located in a different country from where their Ph.D. was conferred.

Augusto received his doctoral degree in biology from the Graduate School of the Stowers Institute for Medical Research in Kansas City, USA. His funded project in Germany focuses on identifying the proteins responsible for generating, transducing, and changing osmotic pressure. He will use a new osmotic sensor developed in the Campàs group to directly measure osmolarity in pancreatic organoids and living tissues.

“In my project, we will investigate the interplay between physics and biology. We understand that biological systems are constrained by physics, and we believe that the evolution of proteins and their regulation led to clever leverage of these physical constraints,” explains Augusto. “We will focus on pancreas development in the mouse, where hollow lumens emerge in ten-day-old embryos and grow to become a complex tree-like structure that carries pancreatic enzymes into the gut. We want to understand how osmotic regulation contribute to this process, and more generally identify physical mechanisms deployed during embryonic development.”

The project will use a challenging but innovative approach of directly measuring physical parameters. It will pair experiments with theoretical analyses to build a model that accounts for dynamic osmotic pressure and cellular feedback mechanisms that shape the organ during development. The goal of the project is to advance the fundamental understanding of embryology and tissue dynamics, and serve as the seed for therapeutic interventions for people who suffer from cystic fibrosis. These patients display increased osmotic pressure in lumen mucus secretions, and there is a need to understand the pathophysiological consequences of changes to osmolarity in the lumen.

HFSP news article: https://www.hfsp.org/hfsp-news/hfspawardees2025

]]>We are issuing a call for expressions of interest and nominations for a director to lead this new field of BioAI Dresden. The successful candidate will be responsible for heading innovative research in areas, that might include, but are not limited to developing AI methods that meet the complexity of living systems, high-dimensional machine learning for biology, AI-driven laboratory automation, and physics- and biology-inspired machine learning. The director will be expected to have a strong research profile in these or related areas and will be supported by a collaboration with the Boehringer-Ingelheim Foundation and the TUD Dresden University of Technology.

Expressions of interest and nominations can be submitted to the MPI-CBG by August 15th.

Please follow the link here for further information.

About Us & the Environment

- About MPI-CBG: https://www.mpi-cbg.de/about-us/

- About the Max Planck Society: https://www.mpg.de/en

- Our Research Areas and Groups: https://www.mpi-cbg.de/research/our-research/research-areas#c5002

Collaborative & Institutional Links

- Center for Systems Biology Dresden (CSBD): https://www.csbdresden.de

- Boehringer Ingelheim Foundation: https://www.boehringer-ingelheim-stiftung.de/en.html

- TUD Dresden University of Technology: https://tu-dresden.de

- DRESDEN-concept (Campus Alliance): https://dresden-concept.de/en/

Working & Living in Dresden

- Working at MPI-CBG: https://www.mpi-cbg.de/join-us/why-mpi-cbg

- Living in Dresden: https://www.mpi-cbg.de/research/scientific-cores-support/supporting-services/international-office

A recent study, led by Theresia Gutmann in the research lab of Anthony Hyman at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG) in Dresden, Germany, published in PNAS, uncovers a novel mechanism that may explain why cGAS stays inactive at the onset of the disease.

To understand how SARS-CoV-2 might interfere with the immune system, the researchers focused on one of the virus’s key structural components: the nucleocapsid protein, which is produced in large quantities in the infected cell. Its primary function is to package the viral RNA genome (a molecule that carries the virus’s genetic code, similar to DNA) so that it can fit into the tiny virus particles. The team investigated the interplay between the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein and the DNA immune sensor cGAS. Biochemical and biophysical experiments revealed that the nucleocapsid protein binds not only to RNA but also to DNA. “This strong binding to DNA was unexpected, as the nucleocapsid protein is a specialized RNA-binding protein that evolved to bind the viral RNA genome. Viral RNA is structurally very different from our DNA,” says David Kuster, joint first author of the study. The viral nucleocapsid protein masks the DNA from cGAS detection, preventing an immune response.

This discovery adds a fresh twist to the repertoire of coronaviral immune evasion tricks. Future research will show whether this trick may be a common tactic used by other viruses to evade the immune system.

]]>Researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems (MPIPKS), and the Center for Systems Biology Dresden (CSBD) have developed a new approach to address these questions, based on an exhaustive analysis of all small interaction networks (of up to five species). Yu Meng, Szabolcs Horvát, Carl Modes, and Pierre Haas analyzed hundreds of thousands of networks numerically and established a mathematical theorem relating the possibility of stability of coexistence in a community to its subcommunities. The authors discovered that even small changes to the network of ecological interactions hugely affect the possibility of stable coexistence.

“We also found that a very small fraction of networks are what we named ‘impossible ecologies’, in which coexistence is simply not possible,” says Carl Modes.

“Our study highlights that it is really the full structure of the network of interactions that determines the stability of ecosystems. Our results can therefore help us to better understand how ecosystems will respond to environmental changes,” summarizes Pierre Haas.

The authors are now collaborating with the mathematics research groups at the MPI-CBG and the CSBD to extend their numerical approaches and results to larger ecological communities using new mathematical tools.

]]>The new research training group will focus on so-called biomolecular condensates – membrane-less structures within living cells that play a central role in the spatial and temporal organization of biological processes. This emerging field of research holds great promise for uncovering fundamental principles of life. In particular, the GRK 3120 aims to investigate how phase transitions and collective interactions among biopolymers contribute to the formation and function of biomolecular condensates. In the long term, these insights may also inspire advances in medicine — for example, by deepening our understanding of neurodegenerative diseases.

RTG 3120 will integrate a broad spectrum of experimental and theoretical approaches across the Dresden research landscape to understand, predict, and precisely control the physics and biological functions of condensates. Furthermore, their specific role in diseases will be investigated, and their potential for innovative therapeutic strategies explored. To achieve these goals, the research group brings together a consortium of outstanding partners: In addition to TUD, the Leibniz Institute for Polymer Research (IPF), the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), and the Helmholtz Center Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR) are also involved.

A central question is: How do proteins and other biological macromolecules cooperate to carry out biological functions at the right time and in the right place? RTG 3120 supports doctoral researchers who are passionate about interdisciplinary science at the interface of biology, physics, and polymer research, and who are eager to push the boundaries of knowledge with curiosity and creativity. Dresden offers a uniquely fertile environment for this endeavor, since it was here that research on biomolecular condensates first emerged: Anthony Hyman (MPI-CBG), Clifford Brangwynne (Princeton University and Howard Hughes Medical Institute), and Frank Jülicher (MPI for the Physics of Complex Systems) discovered the completely new physical principle of biomolecular condensates, which condense cellular interactions between proteins and other biomolecules without the presence of membranes. As a result, Dresden developed a vibrant scientific network spanning cell biology, biochemistry, polymer science, and physics.

RTG spokesperson Jens-Uwe Sommer, Professor of Polymer Theory at TUD and Division Director at the Leibniz Institute for Polymer Research Dresden, explains: "By investigating collective phenomena at the interface of biology, biological physics and polymer physics, we aim to contribute to a new foundation for understanding living matter—and at the same time create an inspiring interdisciplinary environment for the next generation of excellent researchers."

]]>Shiheng Zhao and Pierre Haas from the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems (MPIPKS), the Center for Systems Biology Dresden (CSBD), and the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG) have now shown that elastic shells with complex material properties, like cysts of cells, can behave in new and unexpected ways when subjected to force.

The authors used numerical simulations to show that their exact calculations can even predict the behavior of realistic experimental geometries. Shiheng Zhao and Pierre Haas extended their results to shells under pressure, or “pre-stress,” resulting from the contractility of the cell cytoskeleton to predict the scalings of indentation depth with indentation force.

To test their predictions, the researchers analyzed data from cysts that self-assemble from Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, a mammalian cell line widely used in biomedical research. These cysts serve as simple models of the fluid-filled compartments, or lumina, that form during development. In these experimental data, they found their predicted scalings.

Their work provides a theoretical basis for experimental quantification of the mechanical properties of cysts. Further experimental and theoretical work will be needed to understand how these mechanical properties emerge from different cell biological processes.

]]>A hands-on science station and a public talk by Prof. Stephan Grill, director at the MPI-CBG, will explore the physical laws and mechanisms that biology uses to form and structure life. Whether it's activating DNA, dividing cells, or deciding where left and right are in a quail embryo, we're looking for the driving forces behind it all. Visitors can observe firsthand how new life is formed at our hands-on station in the Hermann-Krone-Bau. The public talk discusses what forces create cells and what role these forces play in deciding which side becomes the left or the right in creatures like the worm or quail.

About the Dresden Science Night

Once a year, Dresden's universities, non-university research institutions, and science-related businesses open their doors to the general public. This year’s topic is “The night that makes you smarter (Die Nacht, die schlauer macht).” Interested visitors will be able to experience science and technology, research and innovation, art, and culture through various lectures, experiments, guided tours, displays, and films. We are looking forward to seeing you this year in the Hermann-Krone-Bau, Nöthnitzer Straße 61.

The full program at the MPI-CBG is available here: https://www.mpi-cbg.de/news-outreach/outreach/lndwdd2025

The program of the Dresden Long Night of Science can be found here: https://www.wissenschaftsnacht-dresden.de/en/events

]]>Before joining the MPI-CBG, Danai will spend one year at the University of Barcelona, Spain, in a research postdoc position funded by Combinatorial Polytope Theory, a joint project between Germany and Spain. During this time, she will regularly visit her colleagues at the MPI-CBG before moving to Dresden in 2026.

The funding for Danai, who received it together with 15 other mathematicians, is part of the Mathematics Program of the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. This program is a collaboration between the the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, which provides the funding, and the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which evaluates the candidates. Eight young Swedish mathematicians, among them Danai Deligeorgaki, will have the opportunity to travel abroad to start a postdoctoral position, while five researchers and three visiting professors from abroad will be recruited to Swedish universities.

“I am very excited about the opportunity to continue my research at the MPI-CBG, and I am thankful to Aida Maraj and Heather Harrington, who have supported me during the application process,” says Danai Deligeorgaki.

The main focus of Danai’s research project is the combinatorics of statistical models that capture relationships between discrete random variables and have applications to algebraic statistics. A simple example examines whether the decision to return a product depends on whether it was bought online or in a physical store based on observed data. The combinatorics of the statistical model can then be used to calculate the probability that the data comes from the model. If this probability is small, it suggests that the model does not adequately explain the data.

These hypothesis tests are considerably more complicated with a greater number of variables, leading to many more contingency tables. This requires the development of advanced statistical models for probability distributions, which utilize methods from algebra, combinatorics, and geometry. Some of the statistical models’ properties will be studied by examining the symmetries of geometric objects, polytopes, which are high-dimensional polygons.

Innovative statistical models will contribute to the development of more efficient methods for analyzing and understanding complex data sets. There are countless applications, ranging from biology and medicine to data processing at large internet companies as well as mathematical phylogenetics, which is one of the areas of interest of Heather Harrington and Aida Maraj at the MPI-CBG.

About the program

Over the years 2014–2030, the program provides SEK 650 million to allow Swedish researchers to receive international postdoctoral positions, as well as the international recruitment of visiting professors and of foreign researchers to postdoctoral positions at Swedish universities. The program also includes funding worth SEK 73 million for the Academy of Sciences’ Institut Mittag-Leffler, one of the world’s ten leading mathematics institutions. Including this year’s grants, 168 researchers have received funding since 2014.

Releated links:

https://kaw.wallenberg.org/en/press/sixteen-mathematicians-share-sek-35-million-research-funding

]]>This year’s participants included runners from the research groups of Rita Mateus, Anthony Hyman, Sandra Scharaw, Meritxell Huch, and Jacqueline Tabler, as well as members of the scientific services and facilities, administration, and the chief operating officer. The nine MPI-CBG teams completed the five-kilometer course, starting at Postplatz, passing the Annenkirche, running through the Wiener Platz tunnel, and finishing at the Rudolf-Harbig stadium.

The team challenge is part of MPI-CBG’s Health Initiative, which supports employeeoyee well-being through physical activity, mental health resources, and preventive care. These efforts are made possible in part through the Max Planck Society’s cooperation with Techniker Krankenkasse.

Congratulations to all participants!

]]>New tissue-derived organoid model: A next-generation organoid model, composed of three liver cell types – adult hepatocytes, cholangiocytes, and liver mesenchymal cells – reconstructs the liver periportal region.

Organoid functionality: The complex organoids, or assembloids, are functional, consistently draining bile from the bile canaliculi into the bile duct as in the real liver due to their accurate tissue architecture recapitulation.

Liver disease modelling: This liver model reconstructs the liver periportal region architecture, is able to model aspects of cholestatic liver injury and biliary fibrosis, and can show how different liver cell types contribute to liver disease.

Vision for the future: These periportal liver models could be used in the future to study the molecular and cellular mechanisms of liver disease. Once translated to human cells, they might enable drug efficacy and toxicity studies in a more physiologically relevant context

The liver has a unique structure, especially at the level of individual cells. Hepatocytes, the main liver cells, release bile into tiny channels called bile canaliculi, which drain into the bile duct in the liver periportal region. When this bile drainage system is disrupted, it causes liver damage and disease. Because of this unique architecture, liver disease investigation has been limited by the lack of lab-grown models that accurately show how the disease progresses, as it is challenging to recreate the liver's complex structure and cell interactions in a dish. Existing tissue-derived liver organoid models consist of only one cell type and fail to replicate the complex cellular composition and tissue architecture, such as the liver periportal region.

The research group of Meritxell Huch, director at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG) in Dresden, Germany, started to address this issue in a previous study in 2021 (Dynamic cell contacts between periportal mesenchyme and ductal epithelium act as a rheostat for liver cell proliferation, Cordero-Espinoza, Lucía et al., Cell Stem Cell, Volume 28, Issue 11, DOI) where the researchers developed a liver organoid, consisting of two cell types, cholangiocyte and mesenchyme cells, which was able to model cell-cell interactions and cell arrangement, but still lacked other periportal cell types – most importantly hepatocytes, the cell which builds the majority of liver mass.

Creating a next-generation organoid model

In this current study, published in the journal Nature, researchers from the group of Meritxell Huch, together with colleagues from the groups of Marino Zerial and Heather Harrington, both also directors at the MPI-CBG, were able to develop a next-generation organoid model, which they named “periportal assembloid.” This assembloid features adult cholangiocytes and liver mesenchymal cells (as in the previous model), but now additionally also includes hepatocytes, which are the main functional cells of the adult liver. This model combines different cells assembled together in a stepwise process one could compare to LEGO.

“Our assembloid reconstructs the liver periportal region and can model aspects of cholestatic liver injury and biliary fibrosis. We chose this region in particular since it plays a key role in bile transport and is often disrupted in liver diseases when the connection of cells responsible for bile transport is blocked,” says Anna Dowbaj, one of the first authors, postdoctoral researcher in the Huch group, and from June 2025 appointed assistant professor at the Technical University of Munich (TUM).

“To achieve our goal, we first created organoids only consisting of hepatocytes that formed working bile channels and maintained key features of real hepatocytes in the tissue. Then, we added cholangiocytes and fibroblast cells to build periportal assembloids. Our liver model works like real liver tissue, moving bile from inside the liver cells into bile ducts, which shows that we were able to replicate the interactions between the different liver cells,” explains Aleksandra Sljukic, also first author of the study and a doctoral student in the Huch group.

By manipulating the number of mesenchymal cells, the researchers were able to trigger a response similar to liver fibrosis. They also were able to show that this model can be used to study the roles of specific genes in liver disease by mixing normal and mutated cells or by turning genes off.

Using topological data analysis, Heather Harrington and her colleagues at the University of Oxford classified assembloids’ shapes and found that some shapes correlated with better liver function over time.

Studying liver diseases and a future vision

Meritxell Huch, who oversaw and supervised the study, concludes, “We are excited that we were able to create a periportal assembloid model that combines, for the first time, portal mesenchyme, cholangiocytes, and hepatocytes. Although some cells are still missing, namely the endothelium and immune cells, the model captures with high precision the cellular and structural architecture of the liver's periportal area at the scale of a tissue culture dish. Additionally, its modular features allow it to be easily studied, handled, and manipulated in the lab. Our liver assembloids are the first all-in-one lab model that can be used to study bile flow, bile duct injury, and how different liver cells contribute to disease.”

Meritxell Huch continues, “We envision that our periportal liver models can ultimately be used to study disease mechanisms. Once translated to human cells, it could be a way of moving from 2D models utilized in pharmaceutical screenings to more physiological 3D models to study drug efficacy and toxicity in a more physiologically relevant context.”

]]>But how do aggregates form in the first place—especially when the cellular environment contains a mix of many different proteins? Remarkably, patient samples often reveal aggregates composed almost entirely of a single protein. This raises a fundamental question: How does one protein "recruit itself" from a complex mixture to form a homogeneous aggregate?

To answer this, researchers Xiao Yan, David Kuster, and Jik Nijssen from the lab of Anthony Hyman at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG) in Dresden, together with collaborators from TUD Dresden University of Technology, Texas A&M University, and the Mayo Clinic in Florida, investigated the behavior of TDP-43, a protein whose aggregation is a defining feature of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD).

Under oxidative stress, cells assemble stress granules—mixed condensates containing various proteins and RNAs, including TDP-43. Over time, the researchers observed a striking transformation: TDP-43 separates from the mix, forming distinct condensates within stress granules. They call this process “intra-condensate demixing.” This demixing was seen not only in vitro and in cell models but also in mouse brain tissue and samples from ALS/FTD patients.

Two factors drive this selective demixing. First, TDP-43 concentration must rise above a threshold. Second, oxidative stress alters TDP-43’s structure, enhancing its self-association and reducing its solubility. Once TDP-43 forms its own condensates, these can solidify over time, creating pathological aggregates seen in neurodegeneration.

“Our work shows that stress granules play a crucial role in disease emergence,” says Xiao Yan. “Targeting intra-condensate demixing of TDP-43 may become a promising strategy for therapeutic intervention.”

]]>ALS is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder that progressively destroys motor neurons, leading to paralysis and, ultimately, death. Despite intense research efforts, treatment options remain limited and largely ineffective at halting disease progression. One emerging area of investigation involves stress granules—membraneless condensates that form in response to stress and typically dissolve once the cell recovers. However, in ALS, some components of these granules, including proteins such as FUS and TDP-43, become abnormally trapped in the cytoplasm and form persistent aggregates. These aggregates are thought to disrupt gene regulation and DNA repair by sequestering key proteins away from the nucleus.

“We were looking for non-toxic compounds that could dissolve stress granules without affecting other cellular functions,” explains Hiroyuki Uechi, the first author of the study. “We found that lipoamide modulates the redox state of specific stress granule proteins. This keeps them from condensing into granules, allowing them to return to the nucleus and resume their normal roles.”

The team demonstrated that lipoamide treatment improved motor defects in both fly models of ALS and human lab-grown motor neurons carrying ALS-related mutations. The findings suggest that modulating protein condensation could be a promising strategy for therapeutic intervention—not only in ALS, but potentially in other neurodegenerative diseases linked to protein aggregation.

The research was conducted in fly models and human-derived neurons grown in the lab. While these findings are promising, they are not yet ready for clinical application, and further studies will be needed to determine whether similar effects could be observed in humans.

This study also reinforces the broader role of phase separation in health and disease, highlighting how tiny molecules can have outsized effects on cellular organization.

]]>“I am deeply honored to have been elected as a member of the Leopoldina,” says Meritxell Huch. “It is a humbling experience to join an institution with such a remarkable legacy of scientific excellence and societal impact. I look forward to engaging with this diverse and distinguished community and to contributing to thoughtful discussions on pressing scientific, political, and social issues. Being part of the Leopoldina is both a recognition and a responsibility, and I am grateful for the opportunity to help advance knowledge and its role in shaping our world.”

Meritxell Huch has done pioneering research on human organoids. Her work has advanced the use of organoid models in drug discovery, screening, and disease modeling for personalized medicine. Organoids are small, three-dimensional, organ-like structures derived from stem cells that grow outside of the living organism. Meritxell and her team have studied the growth and regeneration of animal and human liver and pancreas organoids.

Meritxell Huchs joins current MPI-CBG directors Prof. Anthony Hyman and Prof. Marino Zerial, as well as former MPI-CBG directors Prof. Wieland Huttner, Prof. Elisabeth Knust, Prof. Kai Simons, and Prof. Eugene Myers, as members of the Academy.

Prior to her membership in the Leopoldina, Meritxell Huch was awarded the BINDER Innovation Prize 2019, the GSCN 2022 Hilde Mangold Award, and the Otto Bayer Award 2024, among numerous other honors and awards. In 2023, she was elected as a member of the European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO), and in 2024, she became an honorary professor for stem cell research and tissue regeneration at the Medical Faculty of the TU Dresden.

About the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina

The Leopoldina originated in 1652 as a classical scholarly society and now has 1,700 members from almost all branches of science. In 2008, Leopoldina was appointed to the German National Academy of Sciences and, in this capacity, was invested with two major objectives: representing the German scientific community internationally and providing policymakers and the public with science-based advice. The members from more than 30 countries bring together expertise from almost all fields of research. Each year, about 50 scientists are elected to the Academy for life in a multi-step selection process. Since the academy was founded, more than 7,000 individuals have been accepted into its ranks. Among them were Marie Curie, Charles Darwin, Albert Einstein, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Alexander von Humboldt, Justus von Liebig, and Max Planck. The Leopoldina champions the freedom and appreciation of science. It promotes a scientifically enlightened society and the responsible application of scientific insight for the benefit of humankind and the natural world.

]]>Cross-Disciplinary Fellowships are awarded to applicants who hold a doctoral degree from a non-biological discipline (e.g., physics, chemistry, mathematics, engineering, or computer sciences) and who have not worked in the life sciences before. Together with the HFSP Long-Term Fellowships, they foster the next generation of life science research, last for three years, and on average provide $200,000 USD in total. Fellows work in the laboratory of a host scientist in a country that is different from where their Ph.D. was conferred.

Yuri received her doctoral degree in the area of chemistry from the Pohang University of Science and Technology, Republic of Korea. Her funded project focuses on the internal organization of cells. A key aspect of this process is known as “polarity,” which refers to the way cells establish distinct regions with different molecular compositions. This is crucial for many cellular activities, such as division, movement, and development.

“I am studying these processes in the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans, which shares many biological mechanisms with humans. During early development, C. elegans embryos create a “polarity” that determines the future organization of cells. The protein MEX-5 plays a central role in this process by forming two different regions within the cell: high concentration in the anterior (front) and low concentration in the posterior (back),” explains Yuri Hong and continues, “My project explores how MEX-5 clusters form and contribute to cellular polarity. Using advanced imaging and in vitro techniques, I want to understand the mechanics of cluster formation and function. My work could have potential implications for disease treatment and contribute to a more profound understanding of the fundamental principles that make life possible.”

HFSP news article: https://www.hfsp.org/hfsp-news/hfspawardees2025

Fellowship Booklet: https://www.hfsp.org/sites/default/files/FellowshipBooklet_2025_webversion.pdf

]]>

Maraj’s group, “Algebraic Statistics for Biology,” investigates statistical and biology questions through the lens of algebra, geometry, and combinatorics and develops new math motivated by this perspective. “As someone new to leading a team, I find the support provided by the membership to be highly beneficial for my new role and goals.”

The Elisabeth-Schiemann-Kolleg fosters the careers of female scientists after their postdoc phase, helping them to succeed in their pursuit of a tenured professorship or a directorship of a research institution. The program supports activities that help its fellows establish themselves in the scientific community and offers a platform for transdisciplinary scientific exchange. It offers a range of benefits, including mentoring, networking, and scientific exchange opportunities, to help its fellows establish themselves as leaders in their field.

The Elisabeth-Schiemann-Kolleg is open to nominations from professors and directors of research institutions worldwide. Each year, a call for nominations is published, and the selected fellows are chosen by the members of the Kolleg. The Kolleg is named after Elisabeth Schiemann (1881-1972), a pioneering scientist who was appointed as a scientific member of the Max Planck Society in 1953. She was a courageous woman and a person of integrity who openly resisted the Nazi regime.

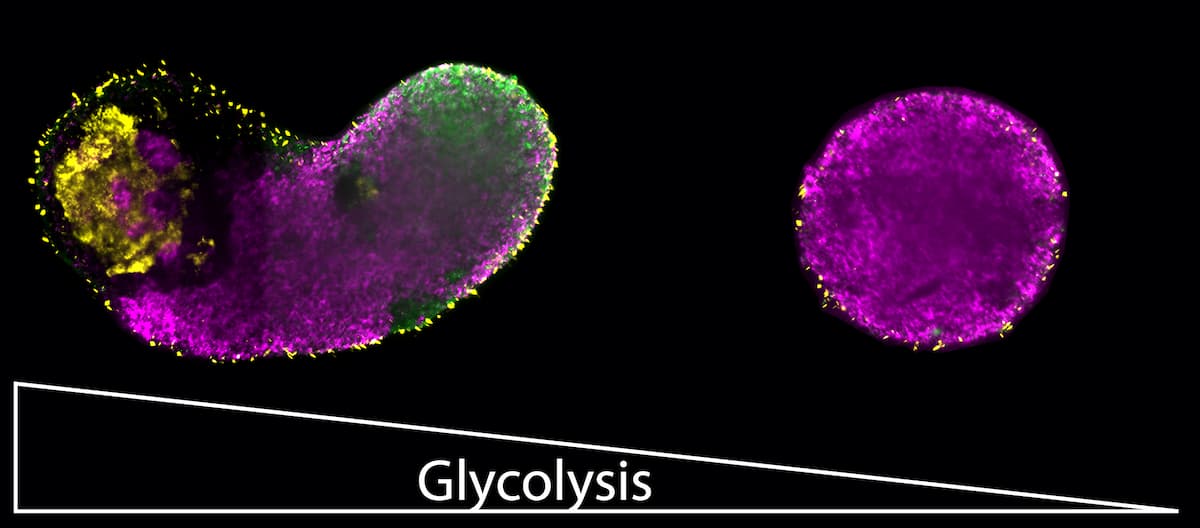

]]>Now, researchers at EMBL Barcelona, Spain, and at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG) in Dresden, Germany, uncover the instructive potential of glycolysis. They show that rather than exclusively providing energy to the cell, glycolysis is able to control, at different stages of early embryonic development, cell fate decisions and the end-state appearance of stem cell-based embryo models.

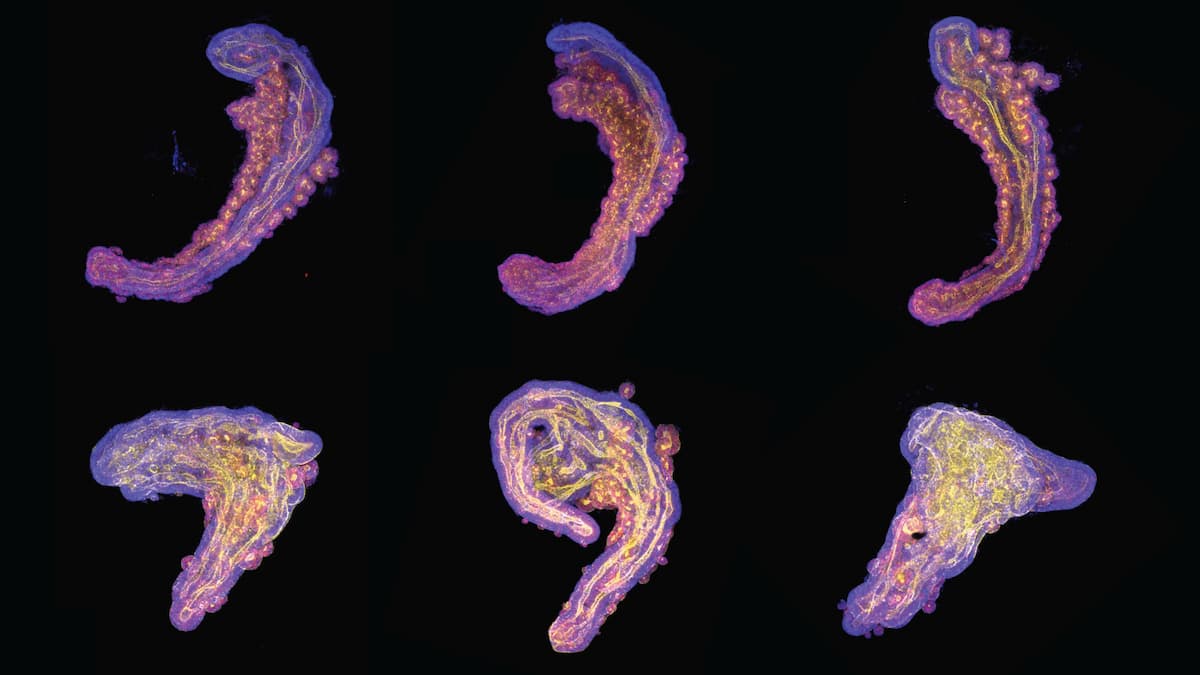

In two back-to-back publications in the journal Cell Stem Cell, researchers from the groups of Vikas Trivedi at EMBL Barcelona and Jesse Veenvliet at the MPI-CBG have used gastruloids and trunk-like structures, in vitro stem cell-based embryo models composed of mouse embryonic stem cells, to study the early steps in the formation of the body plan—a process that lays the foundation for future organ development. Kristina Stapornwongkul, postdoc in the Trivedi group and incoming group leader at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA) in Vienna, Austria, from September 2025, studied the role of glycolysis by changing the glucose concentration in the media where cells live and feed. Alba Villaronga-Luque and Ryan Savill, both doctoral students in the Veenvliet group, studied why some trunk-like structures look more like the natural embryo than others by using machine learning to integrate imaging data with profiles of active genes and metabolites over time and found a critical role for glycolysis.

Stapornwongkul realised that blocking glycolysis disrupted the formation of two important tissue types: mesoderm – which later develops into muscles, bones, or blood – and endoderm – which gives rise to organs like the liver or the lungs. Instead, more cells decided to turn into ectoderm tissue, the type that eventually give rises to our nervous system. This study shows that glycolysis helps activate key signalling pathways (Wnt, Nodal, and Fgf) that guide cells towards mesoderm and endoderm fates. When glycolysis was blocked, the signals weakened and cells developed into ectoderm cells. However, when these signals were artificially boosted, normal cell fate decisions were restored, even without glycolysis taking place. This highlights the crucial role of metabolism as an upstream regulator/activator of specific signalling pathways that influence cellular decisions. Being able to control cell fate through altering media composition means that one could also direct cell differentiation towards the tissue type one is interested in.

“What was most surprising to me was this clear dual role of glycolysis: its bioenergetic function important for growth and its signalling function crucial for cell fate decisions. When we inhibited glycolysis, we clearly saw the loss of the endoderm and mesoderm, but we were able to rescue these cell types by activating the signalling pathways, even in the absence of glycolysis, meaning without restoring growth. This shows that we can decouple glycolysis’s bioenergetic role from its role as an upstream signalling regulator, underlining the existence of two distinct functions during early development,” Stapornwongkul said.

On the left: Glycolysis allows stem cell-based embryo-like models to develop the three germ layers that give rise to many different cell types: ectoderm (magenta), mesoderm (green) and endoderm (yellow). On the right: If glycolysis is inhibited, only ectodermal cells can develop. © Kristina Stapornwongkul

“The exciting thing about Kristina’s work is the hierarchical relationship between metabolism and signalling, at least in the earliest stages of organismal development. This result contributes to an emerging perspective on the relationship between metabolism and patterning, a subject of interest to other labs within EMBL and beyond. From an evolutionary perspective, this is exciting because metabolism predates signalling: even single-cell organisms rely on metabolism, while signalling emerged later in evolution. This has sparked my curiosity about the role of metabolism in the origin of multicellularity. This study marks the beginning of an exciting new direction for my group,” Trivedi said.

Villaronga-Luque and Savill found that early changes in metabolism cause differences in the end-state appearance of trunk-like structures, a stem-cell-based model of embryonic trunk development that forms the tissues giving rise to the spine (mesoderm) and the spinal cord (ectoderm). These structures make it possible to study mammalian embryo development, which is otherwise hidden in the uterus of the mothers, in large numbers of samples without the need for animal experiments. Although many characteristics of these stem cell-based embryo models are similar to those of an embryo, they are unable to develop into fully functional organisms.

A major hurdle for their widespread use is that they are much more variable than the embryo: even when grown under identical conditions, some stem cell clumps develop into structures very similar to the embryo, whereas others don’t. Such variability makes it harder to use them for research purposes that require a highly reproducible baseline, such as disease modelling or toxicity studies. Villaronga-Luque and Savill observed that specifically, the balance between two different processes that produce energy—glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation—affects the variability of the stem cell-based embryo models. With glycolysis, cells make energy by breaking down glucose. The trunk-like structures with a sort of ‘sweet tooth,’ depending more on glycolysis to obtain their energy by breaking down sugar, develop the most similarly to an embryo, whereas the ones that lacked the ‘sweet tooth’ mostly formed ectoderm. Like Stapornwongkul, they found that glycolysis activates signalling pathways like Wnt that influence cellular decisions and, eventually, how much the structures resemble the embryo. Finally, they showed that boosting glycolysis with drugs improved the appearance of the trunk-like structures.

Collage of stem-cell-based embryo models of the embryonic trunk. Those in the upper row have a ’sweet tooth’, depending more on glycolysis to obtain their energy and resulting in a more embryo-like appearance. In contrast, those in the bottom row have less of a ’sweet tooth’, which results in them producing too much neural tissue, and looking less like an embryonic trunk. © Alba Villaronga-Luque, Ryan G Savill et. al / MPI-CBG

“To uncover the reason for this variability in stem cell-based embryo models, you need to have measures early in the development to see what goes wrong. However, such measurements typically destroy the sample, such that we don’t know if it will develop into a successful structure or not. This is the challenge we were able to tackle.” Villaronga-Luque said.

“By combining quantitative imaging analysis with machine learning, we found key characteristics of the structures that can predict how their development will turn out. With this predictive power in hand, we could then investigate the expression profiles of structures for which the end state would otherwise be unknown,” said Savill.

“By being able to predict the future appearance of a stem cell-based embryo model, our team could show that the early metabolic state controls how much the model looks like the embryo, which can be regulated by altering the metabolic activity with drugs. Such predictive power for stem cell-based embryo models and also other types of organoids has the potential not only to help to make new fundamental biological discoveries but also to improve stem cell-based embryo models for applications that require high reproducibility, including disease modelling, genetic screens, and toxicity studies.” Veenvliet said.

These studies mark the beginning of a new paradigm for developmental and tissue biology. It brings metabolism to the spotlight for studying the early stages of development, giving the research community a new tool to study early cell decisions and embryo development. Excitingly, the two studies show that at different stages of embryogenesis, glycolysis acts through a similar mechanism to ensure proper development of the body plan.

The research in the Veenvliet lab was supported by the European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement ID: 101071203 (SUMO – Supervised Morphogenesis in Gastruloids), by the Deutsches Zentrum zum Schutz von Versuchstieren (Bf3R) grant (60-0102-01.P589), and by the Stiftung zur Förderung und Erforschung von Ersatz- und Ergänzungsmethoden zur Einschränkung von Tierversuchen (SET) grant.

]]>Chandraniva Guha Ray and Pierre Haas from the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems (MPIPKS), and the Center for Systems Biology Dresden (CSBD) have now shown that these mechanical instabilities of tissues can be very different from classical instabilities such as the buckling of a sheet of paper under compression: As the compression of a sheet of paper increases, so does the height of the buckled shape. Chandraniva Guha Ray, a doctoral student in the research group of Pierre Haas, explains why this is not the case in a simple theoretical model of a tissue composed of individual cells: “As a tissue folds, the cell sides bend, which causes the top or bottom of the cells to shrink until they cannot bend anymore. This has an unexpected consequence that we called ‘unbuckling’: as the compression increases, the height of the buckled shape can start to decrease.”

Pierre Haas, a research group leader at the MPI-CBG, MPIPKS, and CSBD summarises, “Our calculations prove that this ‘unbuckling’ causes a huge increase of the tissue stiffness. This can be a mechanism for tissue folds to absorb compressive stresses from neighbouring tissues.” One example of a tissue fold that could rely on this mechanism is the so-called cephalic furrow in the fruit fly Drosophila that has recently been studied by the group of Pavel Tomancak at MPI-CBG. Pierre adds, “These minimal mechanical models are useful because they allow us to understand mechanical instabilities in more detail and hence how cell mechanics give rise to biological shape and function at the tissue scale.”

]]>Research group leader Sandra Scharaw and the two postdoctoral researchers Julia Pfanzelter and Émeline Bonsergent discussed their professions and answered questions such as, What is it like to be a scientist? Can you do research while raising a family? Why did you choose to be a scientist? What are your role models? The girls visited the research labs of Eric Geertsma and Mihail Sarov, visited the electron microscopy facility, and enjoyed a panoramic view from the institute roof! The MPI-CBG encourages discussion with interested girls because, even today, female scientists often have a more challenging time in the science world than their male colleagues.

Girls' Day, an initiative of the Federal Ministries for Education and Research (BMBF) and Family Affairs, the Elderly, Women, and Youth (BMFSFJ), is a German-wide campaign that introduces schoolgirls to a variety of careers and activities. Girls are especially encouraged to pursue technical careers in fields where women are still underrepresented, such as "MINT" (mathematics, engineering, natural sciences, and technology).

Tour through the lab of Eric Geertsma © Katrin Boes / MPI-CBG

Early career grants and program grants are awarded to teams of two to four scientists, at any stage of their careers, who embark upon a new collaborative project. HFSP Research Grants support innovative basic research into fundamental biological problems across national and disciplinary boundaries.

"Living systems make guanine crystals for different reasons, like making them to be more sensitive to light (crustaceans) or changing the color of their skin (chameleons). The zebrafish also forms crystals in specialized cells, leading to its brilliant colorful patterns. In our project, my collaborators and I want to find out how this process occurs, considering an essential, but so far unexplored, structure: the lipid membrane that surrounds each crystal”, explains Rita Mateus, who is also an appointed DRESDEN-concept research group leader. Using techniques like CRISPR-Cas9, mass spectrometry, and molecular modeling, the researchers will investigate crystal formation in zebrafish and cell cultures. The results could facilitate the development of therapies to treat diseases where aberrant crystallization occurs, such as kidney stones and gout. The team also plans to contribute new protocols to synthesize organic crystals for a variety of applications in the areas of optics and material science.

The 2025 HFSP Research Grants span the entire spectrum of life science research across the 30 Research Grants and 12 Accelerator Grants that include 104 scientists representing 30 nations. Each grant will last for three years and on average, each award is for $400,000 USD per year. For their awards, the HFSP seeks scientists who form internationally, preferably intercontinentally, collaborative teams, who have not worked together before. In this regard, HFSP fosters frontier research and science diplomacy.

Congratulations to all 2025 winners!

]]>Unlike structured protein regions, where motifs—recurring patterns in protein sequences—are easy to find by using sequence alignments, intrinsically disordered protein regions evolve quickly, and available alignment-based tools are unreliable.

To address this, the research group of Agnes Toth-Petroczy at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG) in Dresden, Germany, and the Center for Systems Biology Dresden (CSBD) has now developed SHARK-capture, an alignment-free tool for detecting motifs in these challenging disordered regions.

“SHARK-capture compares motifs by using amino acid properties without needing strict rules. The tool can identify conserved motifs more precisely than current algorithms. It means it can better find the exact, often very short region of the sequence that is responsible for a certain function,” explains Chi Fung Willis Chow, postdoctoral researcher in the Toth-Petroczy group and first author of the study.

In collaboration with the group of Simon Alberti at the Biotechnology Center of the TU Dresden, he experimentally characterized a newly detected motif in a protein called Ded1p that the Alberti lab studies. “In my experiments, I changed or deleted the predicted motif, which is only four amino acids long. As a result, the protein had only half of the enzymatic activity, corroborating the functional importance of this short motif,” describes Willis.

Swantje Lenz, a postdoctoral researcher shared between the Toth-Petroczy group and the group of Alexander von Appen at the MPI-CBG, joined the project when the algorithm was developed and was ready to be applied. “By working with SHARK-capture, I was able to give feedback to Willis on how to better score and prioritize motifs. Using SHARK-capture, I identified 10,889 motifs across 2,695 yeast IDRs, providing a valuable resource. I found that many recapitulate already existing experimental data,” says Swantje.

“SHARK-capture is the most precise tool for finding conserved regions in IDRs and is freely available as a Python package. Ultimately, we hope that it will enable the discovery of the sequence determinants that underlie the plethora of functions of disordered regions,” summarizes Agnes.

First authors of the study Swantje Lenz (left) and Chi Fung Willis Chow (right). © Katrin Boes / MPI-CBG